Listen now

Part 1:

Part 2:

Join historian Matt Siegfried as we learn how the UAW-CIO came to Washtenaw County at the end of the Great Depression, and through a victory at Ford, led the workers at Willow Run during World War Two, transforming the social landscape of Ypsilanti and bettering the lives of tens of thousands of people.

We will dispel some myths about the “Arsenal of Democracy” as we look at the housing crisis, racism, resistance to unions, and the expendable treatment of thousands of workers. We will look at the role of the labor movement, including Socialists and Communists, in confronting multiple war time crises.

From the rights of women workers to the struggle against segregation, from the fight for housing and services to the campaign to keep open the plant after the war and retain jobs and the community, the activities of those years would shape our region to this day.

Podcast speaker:

Matt Siegfried

Matt Siegfried is a historian, writer and researcher based in Ypsilanti. A graduate of Eastern Michigan University with degrees in History and Historic Preservation, much of his work has been on connecting local history to broad historical moments and trends, with a focus on how race, class, gender, and power impact our social landscape. He has given many presentations at the Ypsilanti District Library, and is a Historian and Cultural Landscapes Expert at the Southeast Michigan Stewardship Coalition, where he works with teachers to integrate place based learning into curricula.

Matt Siegfried is a historian, writer and researcher based in Ypsilanti. A graduate of Eastern Michigan University with degrees in History and Historic Preservation, much of his work has been on connecting local history to broad historical moments and trends, with a focus on how race, class, gender, and power impact our social landscape. He has given many presentations at the Ypsilanti District Library, and is a Historian and Cultural Landscapes Expert at the Southeast Michigan Stewardship Coalition, where he works with teachers to integrate place based learning into curricula.

Treatment of Willow Run Workers

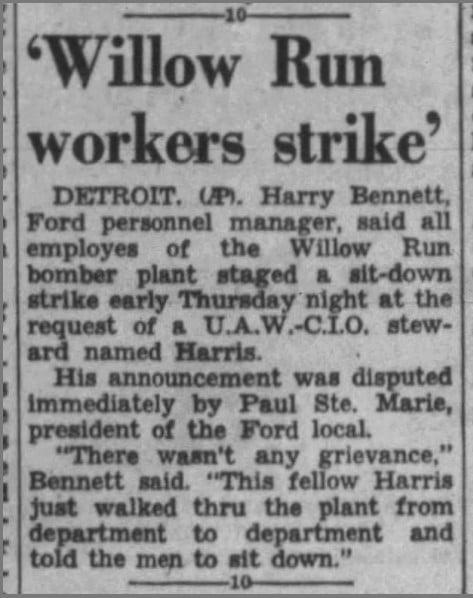

Tens of thousands of people, including whole families, who had migrated from around the country to work at the plant were now stuck without a job, no way to pay rent, and not even a bus ticket home.

As the government negotiated to sell the factory abandoned by Ford to Kaiser-Fraser, it was agreed that former Bomber Plant workers represented by the militant UAW Local 50 would not have seniority rights in rehiring, those rights going to workers from Kaiser-Fraser (coincidentally represented by a much more conservative UAW Local).

The contraction of industry began immediately after World War Two in this area, Kaiser-Frazer would operate the Willow Run plant with a fifth of the workers who previously worked there. When GM took over a few years later, the number employed dropped to 8000. In ten years Willow Run went from employing a height of 45,000 people to employing a height of just 8000 in 1953. Washtenaw county has been losing industrial jobs, not since the 1980s, but since the moment the war ended in 1945.

All through the summer of 1945, Local 50 lobbied and picketed for the government to take seriously the desperate needs of thousands of workers who had helped win the war on the Home Front. But they were as expendable as a battleship

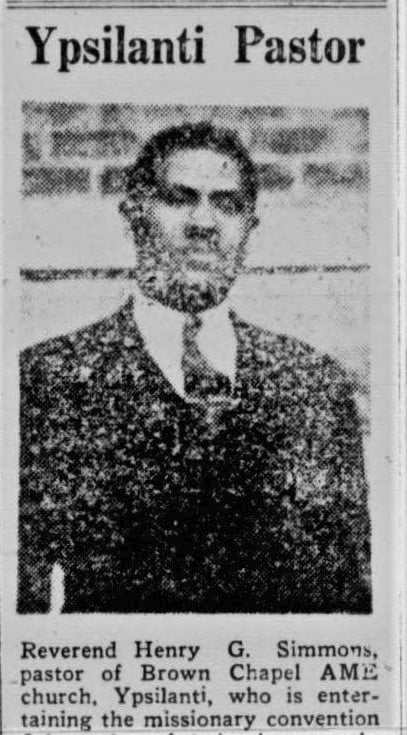

Rev. Henry G. Simmons

Henry Grady Simmons was born in Hampton, Georgia in 1895, to John, a carpenter, and Melissa Simmons. Henry came to Michigan around 1915 and married Ypsilantian, Lucille Crosby in 1918. He would serve overseas in World War One. During the Second World War, Rev. Simmons remembered “fighting for democracy” over seas then, only to come home to the race riots and massacres of 1919’s “Red Summer”. He was determined his own experiences would not be repeated.

Rev. Simmons worked closely with the legendary Rev. Charles Hill of Detroit’s Hartford Memorial Baptist Church in the campaign to get unions to take organizing Black workers seriously. When no other institutions in the city would, Brown Chapel and Rev. Simmons hosted UAW activists in the church basement for organizing meetings. Rev. Simmons even opened the church doors to the local Young Communists, many were also union activists, when they were denied space at the local school.

Some of Rev. Simmons activities include, picketing of Ford hiring offices to demand Black women be employed at the Bomber Plant, picketing Willow Run’s segregated housing being built, holding forums and voter registration drives, traveling to Washington DC with Thurgood Marshall to argue for a change of Federal policy and the desegregation of war industries and housing, which was eventually successful.

Rev. Simmons helped lead the effort to create a Black-led cooperative store, the Progressive Co-op, in the city’s Black south side neighborhood. Rev. Simmons was also instrumental in Ypsilanti’s Black-led Carver Center, which united much of Black Ypsilanti in a social center that also acted as a political platform and organizing center. Eventually the Carver Center would be folded into the Parkridge Community Center.

During the worst of the racial conflict during the war, Rev. Simmons worked with the UAW, the NAACP, local Communists, trade unionists and Quakers to create a series of social spaces where Black and white workers could play music together, discuss union issues and other issues in a safe and supportive space. Without actions like these, the riots and murder of those years could have been far worse.

Rev. Simmons was sometimes vilified in the local Press for his actions, but he was adamant and helped to give voices to so many in this community who had been denied for too many decades. Eventually, Rev. Simmons took a pastorate in Grand Rapids, but returned to Washtenaw where he died in 1951. He is buried in Ann Arbor’s Forest Hill Cemetery

More Names and headlines in the UAW

Use the arrow keys to scroll through the images.

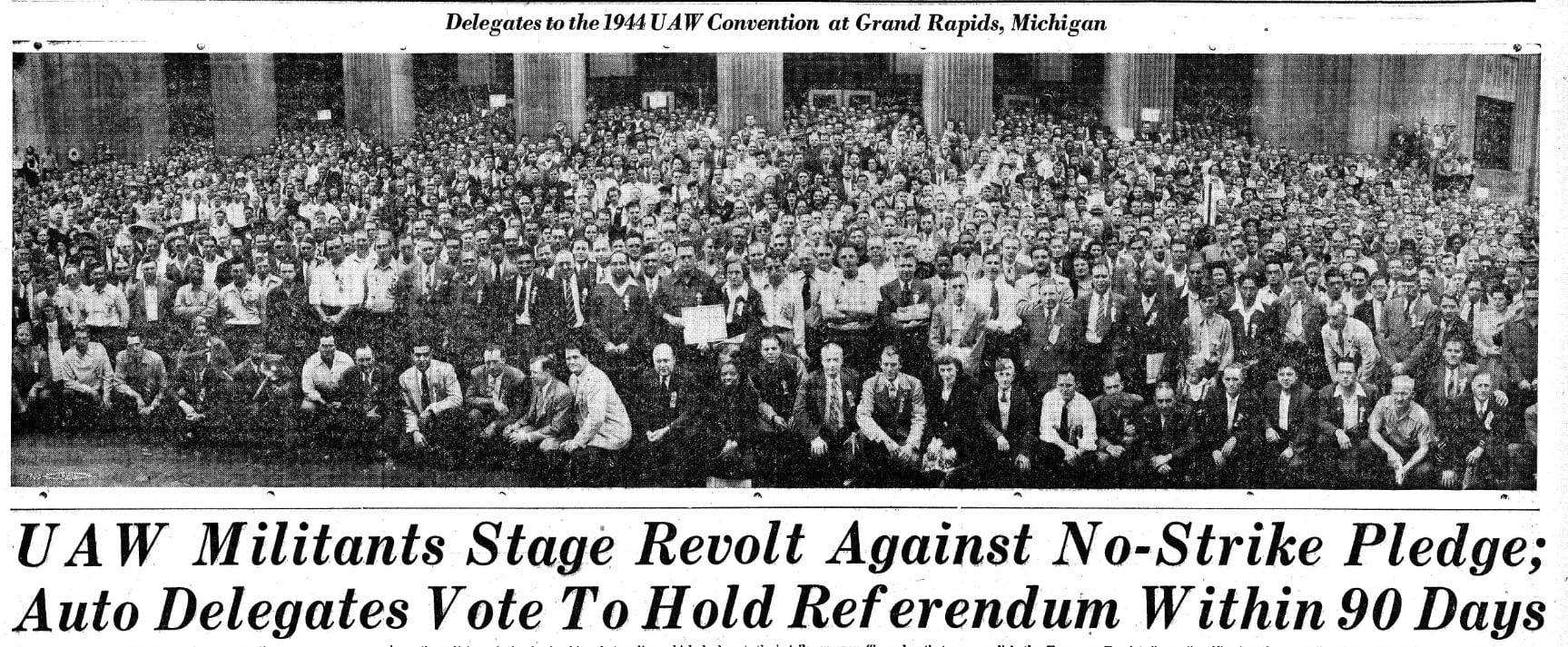

More about the UAW Rank and File Caucus

The “UAW Rank and File Caucus,” was organized at the Michigan State CIO convention in July, 1944 in Grand Rapids. Militants like Larry Yost, chairman of the Aircraft division of Ford Local 600; William Jenkins, president of Chrysler Local 490 of Detroit; Bert Boone, president of Chevrolet Local 659 of Flint; John McGill, former president of Buick Local 599 of Flint, and leaders from Ypsilanti’s 40,000 member Bomber Local 50 spearheaded what would become the most important national democratic opposition in the UAW during the war.

The program laid out in Grand Rapids mainly focused on fighting war-time restrictions on organizing, strikes, and wages and benefits and sought to strengthen democracy and equity in the union. The planks included:

The Willow Run "Rosies"

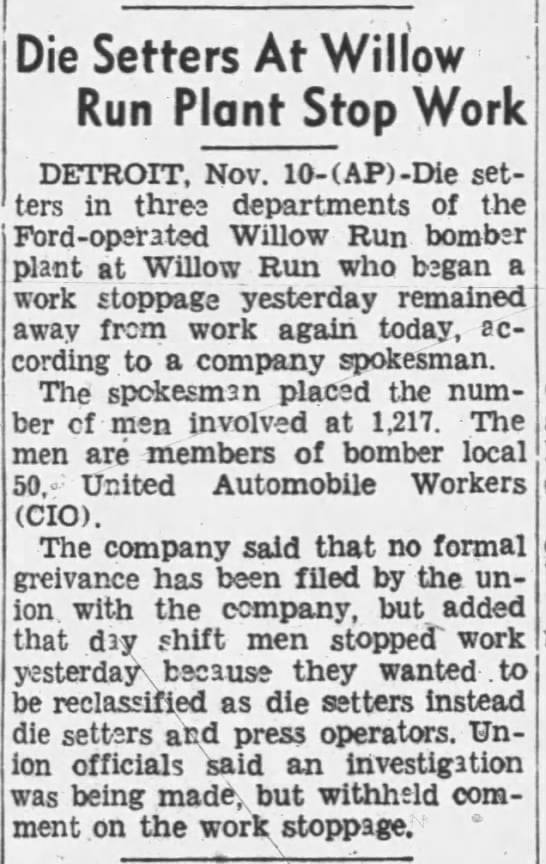

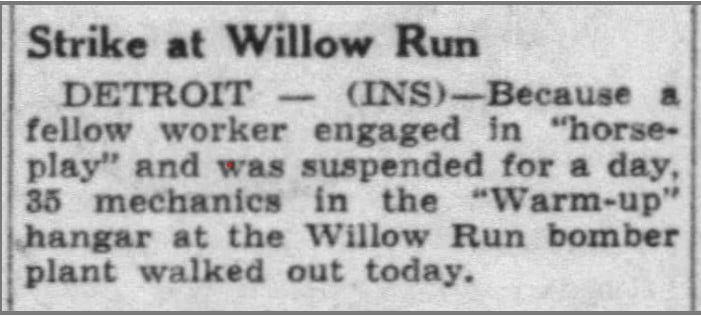

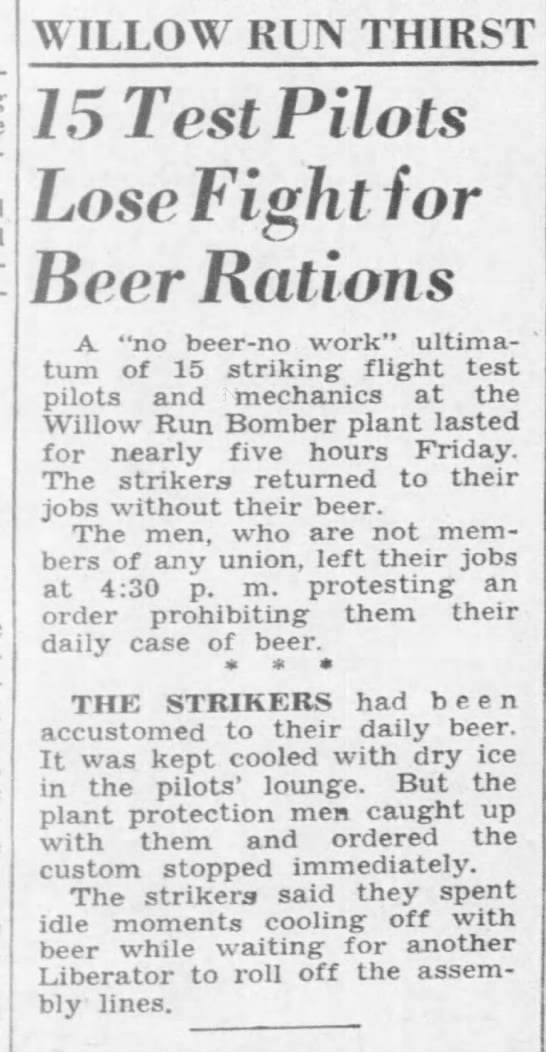

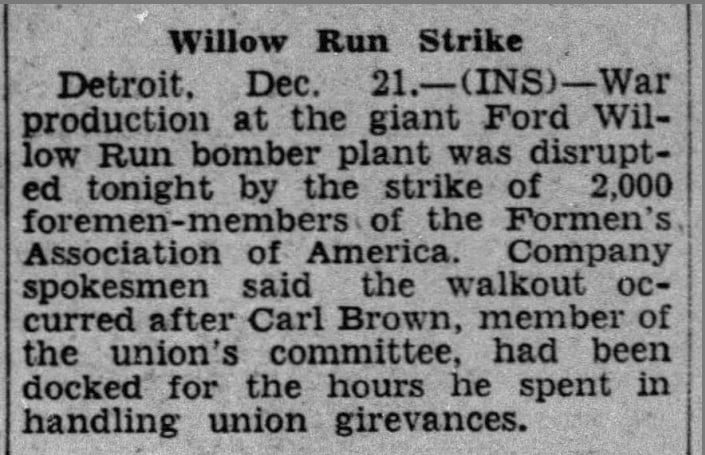

Articles on the Worker Strikes at Willow Run

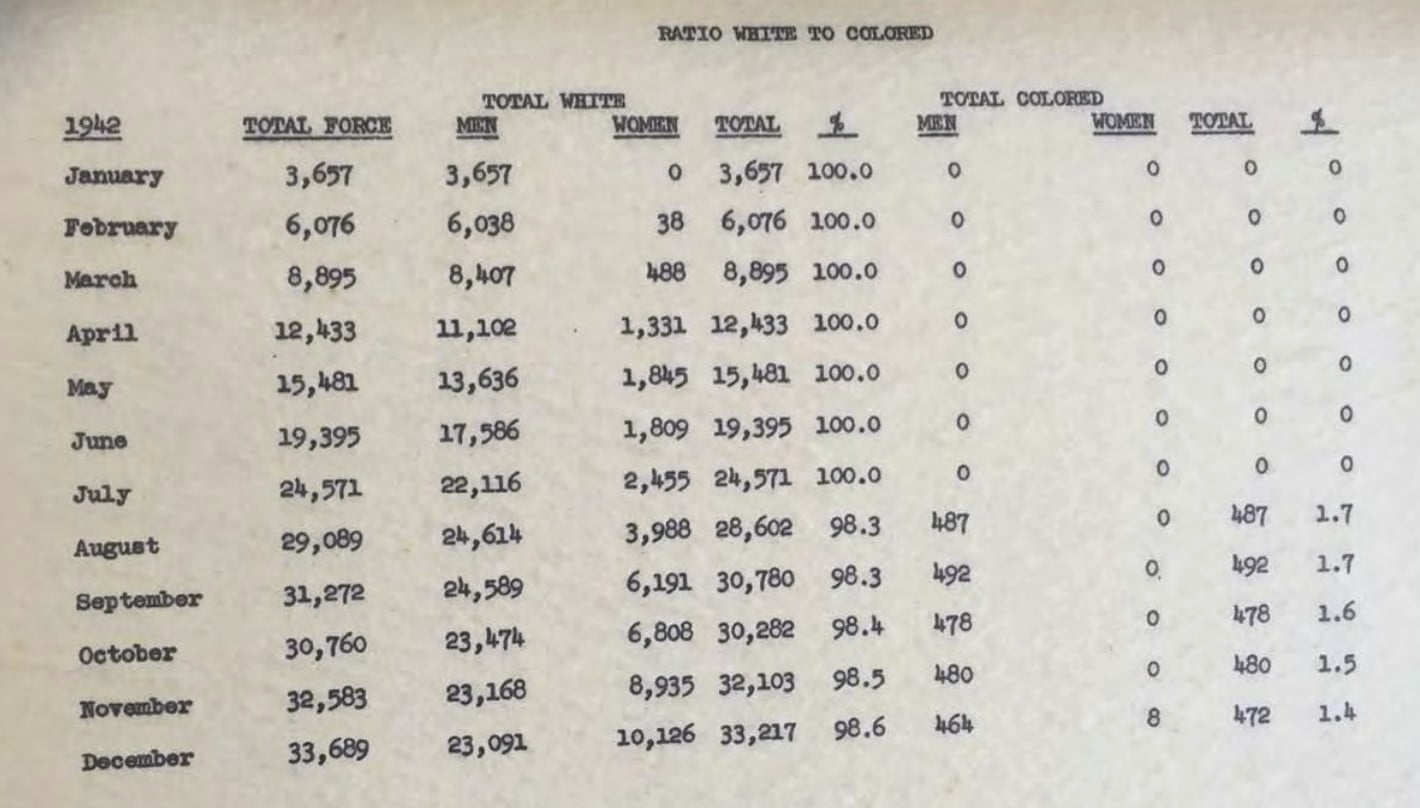

Willow Run January 1942-April 1945 Employment monthly statistics

Highpoint of all employment: June, 1943. 42,331 total workers.

Average white women’s employment: 1942-1945 (40 months), 9,160 or 33%. 1942, 3,668 or 13%. 1943, 14,437 or 40%. 1944, 10,164 or 35%. 1945 (four months) 6,795 or 32%.

Highpoint of all women’s employment numerically: June, 1943. 16,412 (of which 384 were Black), or 38.7%.

Average monthly employment of Black women: 1942-1945, 169 or .6%. 1942, .2 or .03%. 1943, 291 or .8%.1944, 215 or .75%. 1945 (four months), 170 or .8%.

Highpoint of Black women’s employment numerically: April, 1943. 412 or 1% of total (40,752).

Average monthly employment of Black men: 1942-1945 (40 months), 429 or 1.5% total. 1942, 200 or .9%. 1943, 589 or 1.6%. 1944, 489 or 1.6%. 1945 (four months), 455 or 2.1%.

Highest Black male employment numerically: 653 in April, 1943 or 1.6% of total (40,752).

Highest Black employment, male and female, numerically: 1,065 in April, 1943 or 2.5% of total (40,752).

Highest Black employment by percentage was April, 1945. 3.6% (577 0f 16,019).

Average Black monthly employment: 1942-1945, 1.7%