Meet Jermaine Dickerson

Graphic Design Artist and Founder of Hero Nation

My journey begins in the bustling city of Detroit, as a young artist and aspiring superhero. In my bright red cape, I would often fight imaginary foes until I was inspired to translate my heroic adventures on paper. Years later, my passion for art inspired an interest in design.

Meanwhile, my affinity for superheroes has encouraged me to use my superpowers for good through social activism and community engagement— through programs like the SOS Star Program, Ypsilanti District Library’s Summer Challenge, and various youth workshops. I’m also developing my own community initiatives with the Ypsi High Superhero Program and Hero Nation – Ypsilanti, both of which centralize youth engagement, self-empowerment and diversity.

Moving forward, my dream is to continue this work, saving the world one client (and person) at a time.

“We’re on a mission to empower and inspire marginalized youth through comics, video games, and other nerdy things.”

Hero Nation is a nonprofit organization in Ypsilanti, Michigan with the mission to help everyone discover the hero within through events and programs based in nerd culture that foster empowering, creative, and educational experiences for underrepresented and marginalized communities — including people of color, LGBTQ people, people with disabilities, women, and people with low socioeconomic status. We believe things like superheroes, comics and video games can be used as tools to inspire social change.

SOCIAL JUSTICE LEAGUE COMIC STRIPS

Join Jermaine in his mission to help all kids use graphic novels as a way to express themselves and/or speak up for justice and diversity.

Talk with your kids about graphic novels and comic strips–what do they like about reading that format, why? Share your opinions too.

Talk about how visual images and texts can work together to communicate messages about social justice and history. What do graphic novels or comic strips have to offer that other mediums may not—or at least, not to a similar extent?

Graphic novels and comics can be an effective tool to defend what is fair or right in the world, to speak out against stereotypes or to teach important historical lessons.

MAKE A SOCIAL JUSTICE COMIC

Work as a family or separately depending on the age of your child. Start by exploring these questions as a family.

- How are graphic novels and comics created?

- How can graphic novels and comics promote social justice?

- What social justice issues would you like to convey in a comic strip?

- What plotline and kinds of characters will you feature?

- What personal experiences could you draw from to create your comic?

Now create an outline or sketch of the comic. You can find examples of different templates that you could start with here.

Create drafts of pictures and stories. If you’re using paper, work in pencil first so you can erase or edit any sections.

Talk together, revise, edit and then finalize the comic strip. You may or may not choose to add color depending on the message you choose to convey.

If you don’t consider yourself an artist, learn more about free technology you can use on a phone to make a comic like the one to the right created by two brothers at a library workshop.

After the comic is finished, explore these questions together as a family.

- What social justice issue do you hope people will think about after reading your comic?

- What do you hope people will gain from reading your personal story about (in)justice or (in)equality?

- How might readers react to your comic? Why?

- Do you think your comic will inspire activism and action?

Activity adapted from Teaching Tolerance.

LEARN ABOUT GRAPHIC NOVELS BY BLACK AUTHORS AND ILLUSTRATORS

AFROFUTURISM VS. AFRICANFUTURISM

The newest versions of Black Panther and Shuri are both great examples of Afrofuturism. Afrofuturism seeks to reclaim black identity through art, culture, technology, and political resistance. It is a way of viewing possible futures or alternate realities. Afrofuturism is a reflection of the past and also a projection of a brighter future in which Black and African culture shines brightly through white dominant culture.

Fantastic Four (July 1966)

The first Black superhero in mainstream American comic books was Marvel’s Black Panther, who first appeared in Fantastic Four #52. Written by Stan Lee and illustrated by Jack Kirby.

Black Panther (2016- Present)

Written by MacArthur Genius and National Book Award winner Ta-Nehisi Coates and illustrated by Brian Stelfreeze.

Shuri (2018- Present)

The Black Panther’s tech-genius sister launches her own adventures — written by best-selling Afrofuturist author Nnedi Okorafor and drawn by Eisner-nominated artist Leonardo Romero.

NNEDI OKORAFOR

Africanfuturism is similar to “Afrofuturism” in the way that Blacks on the continent and in the Black Diaspora are all connected by blood, spirit, history and future. The difference is that Africanfuturism is specifically and more directly rooted in African culture, history, mythology and point-of-view as it then branches into the Black Diaspora, and it does not privilege or center the West.

Africanfuturism is concerned with visions of the future, is interested in technology, leaves the earth, skews optimistic, is centered on and predominantly written by people of African descent (black people) and it is rooted first and foremost in Africa. It’s less concerned with “what could have been” and more concerned with “what is and can/will be”. It acknowledges, grapples with and carries “what has been”.

Africanfuturism does not HAVE to extend beyond the continent of Africa, though often it does. Its default is non-western; its default/center is African. This is distinctly different from “Afrofuturism” (The word itself was coined by Mark Dery and his definition positioned African American themes and concerns at the definition’s center. Note that in this case, I am defining “African Americans” as those who are direct descendants of the stolen and enslaved Africans of the transatlantic slave trade).

READ AND REFLECT

If you read part one of the Anti-Racism series, you know there aren’t enough youth books with characters of color published each year. What about BIPOC authors writing from their own perspectives? The lack of BIPOC authors is even more evident when looking at graphic novels. But there are more added each year. Click the button above to find some available at our library you can read to get inspired to make your own.

REFLECTION

Our mission as a community must be to work collectively to honor the power of all young people and empower them to embrace and express their whole selves. This will help us to authentically work alongside one another as we imagine and create a better future for all.

Click the button below for a reflection activity to help guide your family’s next steps.

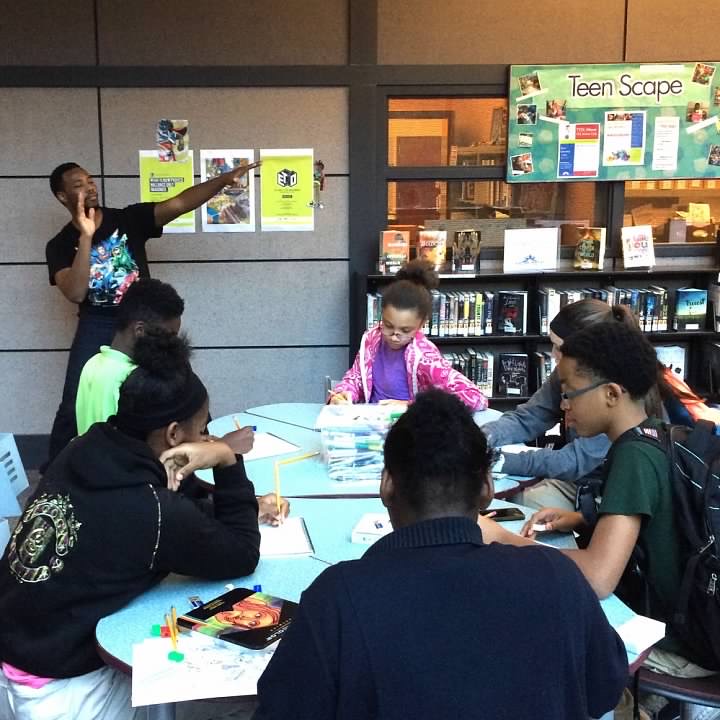

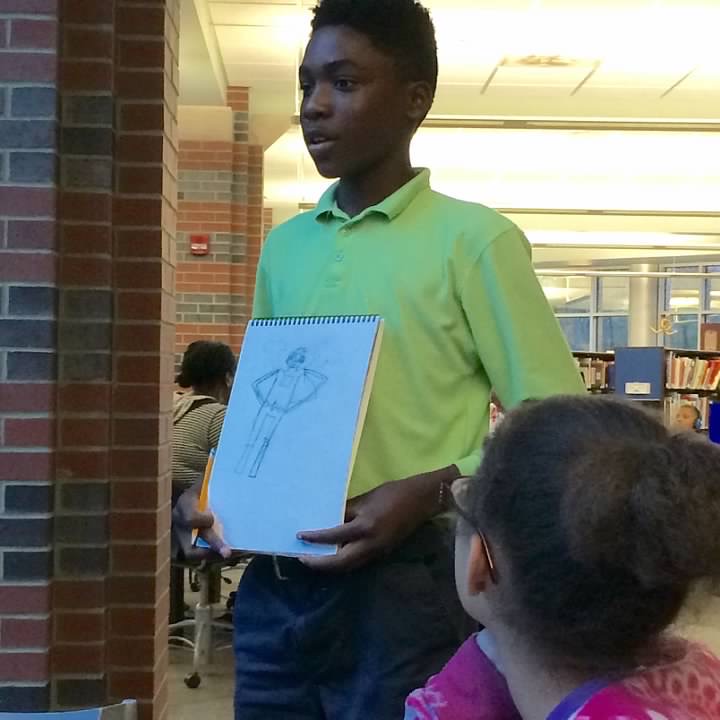

MORE ABOUT JERMAINE IN THE COMMUNITY

Jermaine has taught Create Your Super Hero Self-Portrait Workshops at both YDL-Whittaker and YDL-Michigan. Watch for more chances to learn from Jermaine at the library and in the community!

LEARN MORE ABOUT ANTI-RACISM

In a racist society it is not enough to be non-racist, we must be anti-racist.

– Angela Davis

Get tips for how to talk with your kids about race and racism.

FUN FACT

Jermaine designed our Summer Challenge logo!

If you missed last week’s anti-racism webpage, click below to meet the women who founded Black Men Read and learn how to use books to talk about race and racism as a family.

The Town Hall Anti-Racism Series is Co-Presented by Kekere Freedom School.